Part 4 in our series, “Why Do People Hate Their Boss”

People everywhere want to be freed from leadership styles and management models that continue to make them feel like slaves to machines. Peter Senge’s modern Machine Metaphor (discussed in Part 3 of this series) describes an institutionalized cookie-cutter model that can be seen in every business sector, from schools to corporations to healthcare. So how can learning more about Henry Ford’s practices and the machine metaphor teach us about the employee engagement challenges today?

For today’s workforce who are looking for personal growth in their careers, this mechanical approach, void of human emotions and operating strictly in red and black ink or zeros and ones, usually leads to employee discontent, mistrust, and a lack-of-care attitude as blowback. Gallup’s most recent State of the American Workplace report shows that 68% of the nation’s workers are disengaged from their jobs, the majority feeling enlisted with no power or influence.[1]

The Machine Metaphor, it turns out, is not new at all. In fact, it’s historically rooted in the first machine age, which most historians agree began with the game-changing technology of the steam engine. Remember your high-school history books and the beginning of the Industrial Age? You might remember James Watt, who in the second half of the eighteenth century innovated and improved the steam engine into a massive roaring mechanical power that harnessed the muscle of 200 horses and profoundly changed the world. It was the steam engine that led to mass transportation, factories, and mass production.

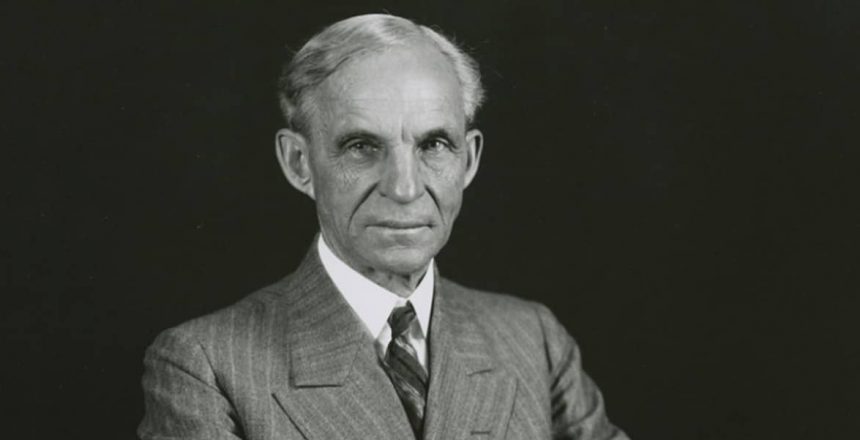

By the turn of the Twentieth century, the rise of capitalist industrialists not only advanced things technologically, but some had a profound sociological impact on society. For example, historians maintain that to understand America in the Twentieth century – and arguably today in the Twenty-First century – one cannot underestimate the ideological impact that car manufacturer Henry Ford had on American business, culture, and even the way we think.

Like James Watt before him, Ford innovated. He so dramatically improved efficiency in the factory assembly line that he revolutionized the car industry and, of course, mass transportation. But Ford went much further than that by superimposing his industrial model of mass production onto people – not only as a way of living but as an established societal norm that developed into the Efficiency Movement of the Progressive Era.

Although Ford was considered by many to be philanthropic and paternal towards his factory workers, in the spirit of ‘scientific management,’ he patently ignored the social aspects of work. Creative and innovative ideas were monopolized by management because, in Ford’s mind, knowledge equaled capitalist production power. And Ford was right: innovation today still equals competitive power. Otherwise, industrial work was repetitive and demoralizing for employees, dehumanizing workers to machines. The workplace was – and still is in most cases – steeply hierarchical and overly bureaucratic. Ford made the rules and did all the thinking. Workers were expected to follow orders without thinking. Management authority was sovereign.[2]

In the early Twentieth century, during the time of Ford’s revolutionary Model-T production (1908-1927), most workers, like Ford’s assembly line workers, were unskilled immigrants with very little education. Assembly line jobs required little training, and Ford wanted it that way. He was diligent in removing “the necessity for skill in any job [that is] done by one,” as he described in his autobiography My Life and Work. Ford was, of course, wary of the disruptive power of the ‘proletarian masses’ and operated with a dual philosophy of labor: workers were ideally mindless automatons but also persistent foes of capitalist command and control.[3]

What made Ford different from other industrialists of the time and from the robber barons of the late Nineteenth century was his paternalistic care and desire to create a better life for his worker. Ford embarked upon an even larger social vision to rehabilitate the working class. He began by instituting the The-Five-Dollar-Day, which at the time shocked many because of the unprecedented decision to increase the wages of his workers to double that of the car industry standard at the time. It was a move that increased productivity.

But, while Ford’s workers were paid generously – more than any others – in return, they were expected to submit to more regulations. In addition to loyalty and hard work, employees were expected to adhere to moral and ethical obligations, exhibit wholesome habits and fulfill responsibilities in family life and personal behavior, both inside and outside of the factory.

Ford set up a ‘Sociological Department’ to teach, on the one hand, behaviors that Ford felt would make better people, such as how much money to save, how much to spend, how to stay clean, and what children should do. On the other hand, the department was a strong arm for compliance and risk management that would, as Ford wrote, “guard against an employee’s prosperity injuring Ford’s efficiency.”

The Sociological Department initiated a surveillance program of employees by hiring sociological investigators whose job it was to search for and identify those who were not following the strict company protocols. In January of 1914, one-hundred investigators were hired. By the end of 1914, another hundred had been hired. This form of spying and policing developed into including midnight ‘raids’ on employees’ homes.[4]

The intrusion into the private lives of Ford employees has prompted historians to speculate whether Ford’s social reform was legitimate or whether he was simply extending corporate control. By 1921 production managers began to object to the constant scrutiny of workers’ lives and behaviors, a pushback that later evolved into the formation of workers’ unions.

Undaunted, Ford proactively institutionalized his vision for humanity by founding several schools for not only his workers but other working-class families. Under the rationale of improving working-class lives, Ford built three models of efficient mass production: technological, sociological, and institutional models that endure today. Ford wrote in his own words that these models symbolized “the fusing process that makes raw immigrants into loyal Americans.”[5]

As author Steven Watts points out in recommended reading The People’s Tycoon: Henry Ford and the American Century, though a subtler form of authority than the older model of the robber barons, a perhaps more sinister form of social control was nevertheless shaped by a wealthy and powerful industrialist. Watts sums it up:

“Ford wanted to manufacture men as well as cars. There was a mechanistic view of human nature that mirrored the sensibility of the surging auto industry. Human beings were viewed as machines that needed tune-ups to run smoothly and productively-a mechanistic metaphor that unfolded relentlessly-man was an engine of enormous power if managed scientifically.”

Today’s workforce is obviously not the uneducated and untrained labor force from over a century ago, and yet employees today, in many cases, are being led and managed as if they were. People and employees-even managers-who are highly educated, trained, and Internet connected feel insulted by being treated on a need-to-know basis, the verdict usually being that they don’t need to know. The surprise is that the disengagement and the distrust that employees have for their bosses, managers, and organizations are rooted in the obvious incongruence of Industrial Age Machine Metaphor management models still being used today.

Now that we’ve learned more about the machine metaphor, in Part 5 of this series, we will explore Agency Theory and its impact on organizations today.

[1] Gallup State of the Workplace Report https://news.gallup.com/poll/181289/majority-employees-not-engaged-despite-gains-2014.aspx

[2] Devon G Pena 1997 The Terror of the Machine: Technology, Gender, and Ecology on the U.S.-Mexico Border (Austin TX: Center for American Mexican Studies, University of Austin)

[3] IBID

[4] Steven Watts 2009 The People’s Tycoon: Henry Ford and the American Century (New York: Vintage Books, a Division of Random House, Inc.)

[5] IBID